Smashed at the Weekend #14: Victor Garvey at The Midland Grand

a restaurant review/report/interview type of thing. I don't know.

Somewhere to go: Victor Garvey at The Midland Grand, London

I love eating tasting menus. What I don’t love is writing about tasting menus, or reading about other people eating tasting menus. When you are there, in the moment, luxuriating in one incredible dish after another, each with a paired wine that tastes like nectar, it all seems magical. But relating that experience after the fact is like telling someone about your dreams; when put into words your so-vivid-it-felt-like-real-life nighttime adventure becomes duller than an episode of Antiques Roadshow (apart from the exciting auction bit at the end, obvs).

So, how to do proper justice to a recent lunch at Victor Garvey at The Midland Grand without resorting to a plodding description of a procession of dishes? I’m meant to be a professional food writer, surely I can describe the seven-course ‘Menu Experience’ without boring the pants off everyone? Let’s try this. Victor Garvey is the William Forsythe of gastronomy. That’s a pretty pretentious statement, I grant you, and a slightly odd, left-field comparison to make. It’s one I never would have thought of had I not attended a performance of The Forsythe Programme at Sadler’s Wells a few weeks after my lunch at Garvey’s gaff.

William Forsythe is an American dancer and choreographer, born in New York. ‘Forsythe has consistently investigated ballet’s technique . . . .He has also enlarged our ideas of what the art form can encompass,’ says dance critic Roslyn Sulcas. ‘Victor Garvey is an American chef and restaurateur, born in New York. Garvey has consistently investigated culinary techniques. He has also enlarged our ideas of what fine dining can encompass,’ says Smashed publisher Andy Lynes.

Am I reaching a bit here for the sake of a convenient analogy? Maybe, but there is undeniably something distinctly American about Garvey’s approach at The Midland Grand (and even more obviously so at his Californian-inspired Sola restaurant in Soho). Like Forsythe, whose style has been described as ‘both respectful and revolutionary’, Garvey uses the classical techniques of his craft/art, but is not hidebound or restricted by them. It echoes the bold experimental approach of US chefs like the late Charlie Trotter or Grant Achatz, although Garvey’s food is unlike either. It’s the American pioneering, can-do, anything-is-possible spirit I’m talking about.

So, just how similar is eating great amberjack crudo with avocado, leek and elderflower to watching a performance of Forsythe’s Playlist (EP)? How far can I stretch this conceit until it snaps like the Achilles tendon of a ballet dancer who failed to warm up properly? English National Ballet First Soloist Precious Adams says that, with Forsythe’s style, she’s ‘constantly trying to push the absolute end of your own line and physicality. So you’re definitely not inside a box – you’re trying to get to the far corners of the box’. With his crudo, you could argue that Garvey is trying to get to the far corners of the fine dining box by serving the buttery raw fish with a soy, roasted fish and vinegar-based sauce that’s been infused with blackened leeks and roasted soya beans. It’s the same thing, see? Well, sort of.

I should note at this point that by focusing on the Americanness of Garvey’s cooking, I’ve overlooked a key aspect of the menu at The Midland Grand. I’ll let Garvey himself explain:

‘I've got about nine different nationalities in me, and I don't feel particularly at home anywhere and so that kind of translates to the cooking. I can't not cook my style, but Sola draws more on what I remember from America and working in America and and Midland Grand draws more on my French and, to a certain degree, Spanish heritage. They're all coming from the same mind, but I'm looking at different parts of my culinary library when doing ideas for each.’

As his biogrpahy on the Midland Grand website explains, Garvey was ‘born to a Spanish/French mother and a first-generation American father (of Ukrainian and Irish heritage)’ and his career has taken him to Spain (including El Bulli), Copenhagen (Noma), California and Las Vegas. So it’s complicated, a bit like the trio of canapes based around tomato, onion and peppers that kicked off our meal in the stunning and ornate high-ceilinged dining room that reminded me of the last time I ate in a three-star in Paris. It’s worth describing the canapes in some detail because they demonstrate the lengths Garvey is willing to go (or willing to ask his team to go to I suppose) in order to give people a good time. Or maybe he’s just amusing himself, who knows. Either way, the end result is something quite spectacular.

Shall we pretend that my palate is so incredibly sensitive that I was able to detect every ingredient and that my culinary knowledge so extensive that I was able to discern every step and process in their creation? Or would it be better to admit I gobbled them down, thought they tasted amazing, especially with a glass of Birgit Eichinger Gruner Veltliner 2023, and ask dear old Victor to take us behind the culinary wizard’s curtain and explain how he prepares ‘The Mediterranean Garden’ which is what he calls the set of canapes. I mean, I did spend half an hour on the phone quizzing him about his food. So yeah, let’s do that.

‘The tomato is from a producer in Provence called Hubert Lacoste. He produces the most amazing tomatoes that I've tried in the UK. They're unconscionably expensive - we're talking like forty quid a kilo - but they're totally worth it. It's dressed in a sweet and savoury tuna garru,m which we make from mojama, a cured tuna. We make a stock with it, heavily reduce that stock, add some colatura anchovy extract, a little bit of honey, some vinegar and some olive oil. We vacuum seal everything, let it sit and then strain it out. It’s topped with tomato sorbet and fermented gazpacho water poured around it.’

‘The pissaladière is my favourite. It's a brown butter brick pastry tart with black olive praline at the bottom. The black olive praline is the same concept as taking a caramel and then putting some roasted hazelnuts in there and blending it up. We do the same, but instead of hazelnuts, we use dried Moroccan black olives. The texture is the same, but it's got all the umami and headiness of the black olives. There’s a salted butter disc, and then a mousse of caramelised Cévennes onions coated in black olive jelly. You've got a bit of finger lime on there, and some Ortiz anchovies and flowers and herbs for a little bit of herbaceous, refreshing crunchiness. There's some raw Thai baby shallots sliced really thin. I think raw alliums are a fantastically underused ingredient in fine dining; everybody's too scared of their breath. The beauty of any onion raw is the astringency, it just cuts through a lot of stuff in a way that you can't with lemon or vinegar.’

‘The last one is the pointed pepper. We get in some unbelievably good Cornish mackerel, salt it and cure it for a day and then cold smoke it. We make it into a pate with homemade mayonnaise, crème fraîche, crème crue, chives, lemon, shallots, cornichon and a bit of gelatin just to make it hold its shape when we dip it in the piquillo pepper gelee. On the bottom, it’s a piperade (a kind of pepper jam), confit Yukon gold potato and a little brioche croute.’

We could go on like this for some time, there was a lot of food that could use a lot of explaining. Like ‘Le Homard: Whole Native Lobster with Sand Carrot and Osmanthusthe’, a highlight of the meal and a must order (at the time of writing, it’s on the a la carte or Menu Gourmandise). Do you really need to know that it comes with a sauce made from a stock made with the roasted heads and shells of the lobster that’s cooked for two days and finished with coconut milk, ginger, lime leaf and osmanthusthe, a naturally occurring sugar-free sweetener used in Chinese cuisine? Or that it comes with a seafood boudin of prawn, scallop and lobster knuckle that’s whiskey flambéed at the table? Of course you don’t, that’s too much info. Just stop now, I hear you cry.

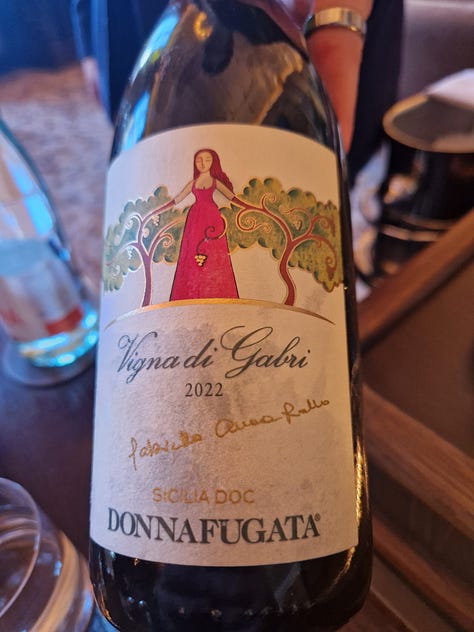

But before I go, I have to say a word or two about sommelier Seyit Ali’s wine pairing, which was expertly done, with a lightness of touch and a great deal of good humour. Each wine added something to the experience. It appeared as much care and attention had been taken over selecting the right wines as there had been in creating the food. I’m not sure the chefs would agree with that, as they slave away coating onion mousse in black olive jelly, but you know what I mean. Here’s what we drank:

By comparing Garvey to Forsythe, I’ve positioned him as a pioneer and innovator. I’ve been writing about fine dining long enough to know that’s probably not a very sensible thing to do. Ideas have been circulating the global haute cuisine scene like a virus for at least the entirety of this century, so who the hell knows where a dish, an ingredient or a technique first appeared. So I’ll make no grand claims on Garvey’s behalf. What I will say is that I had the same feelings after lunch at The Midland Grand as I did after that matinee at Sadler’s Wells: in their different ways, both Garvey and Forsythe know how to uplift the human spirit. Don’t you just love Americans?

The Details

Victor Garvey at The Midland Grand, St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel, Euston Road, London NW1 2AR. 020 7341 3000; midlandgranddiningroom.com

Main courses from £32. Tasting menus from £139

Smashed dined as guests of The Midland Grand.

Phenomenal write up, Andy. Thank you for sharing. I love your comparison with Forsythe.

adding to my list on Beli. also agree, that dining room is divine