This edition of Smashed is free to read. If you’d like to support my work, use the button below to buy me a coffee.

Ben Tish has been Chef Director of Sam and Georgie Pearman’s Cubitt House London pub group since 2022. He oversees eight pubs across Belgravia, Chelsea, Marylebone, Mayfair and Notting Hill, including The Alfred Tennyson, The Thomas Cubitt and The Orange. He began his career in the early 90s in his home town of Skegness as kitchen porter to a young Jason Atherton and has since gone on to hold several prestigious positions, including Chef Director of the Salt Yard Group in London. He is also an acclaimed cookbook author. His latest book is Mediterra and you’ll find three recipes from it below.

Over a very enjoyable lunch at The Orange (see below for details of what we ate) I asked Ben to select five pivotal dishes from his career that chart his evolution as a chef and restaurateur. For each dish, we talked not only about how the dish was made but also about Ben’s memories of the times, and thereby built up a picture of his life in the restaurant industry. But before delving into his history, I asked him about his current role at Cubitt House.

‘It was quite a chunky project at the beginning because we were basically starting afresh. The executive group was put together right at the end of COVID. I started a bit later than the others. I was still tied to my last place, The Stafford. There were five pubs when we took over, and now there's eight. There should be nine by the end of the year.

The existing portfolio, we've refurbed. We've done it project by project, starting with The Orange, which is the original pub. Then we added on The Princess Royal, The Barley Mow and The Builders Arms over in Chelsea. There’s been a few sleepless nights, but we're in a really good place now, and we’ve got a good team. We've got 400 staff across our pubs, obviously not all chefs. There's a lot of people and I enjoy the scope. You've got to be of a particular mindset, otherwise you just drive yourself mad. You can't micromanage, you've got to delegate. I have a small team beneath me - an executive pastry chef, an executive chef, a group head chef and a food cost supplier manager. I prioritise food, which, if I didn't have the team, I wouldn’t be able to. That's what interests me, and that's where I think I can add value. I know I can't add value on the admin and things like that, that's not my forte.

I've always liked pubs. In my early days in London, when I was working with Jason Atherton, I lived on Herbal Hill in Farringdon. We worked every day, except Sunday, when we’d go to The Eagle. We’d get in there as soon as we could and stay there all day until they closed early evening. I absolutely loved it.

I wasn't phased by the fact that I was going into pubs for the first time in my career with Cubitt House because we were very clear that we would want to be food-led and that each pub would have its own identity. All the menus are different across the group, which is exciting for me. I don’t want it to be a chain. Some of the menus are more Mediterranean, which is my natural habitat for food, and then the ones in Mayfair and Marylebone are more like a chop house. There’s a classic boozer on the ground floor with Scotch eggs and pies and all that, and then a dining room upstairs with a lot of protein, a lot of sides, and sauces that you can add on.

I feel like there's more of an appetite again for the pubs, but in a new way. People are probably expecting a bit more from places now. We don't ever stand still. It is a tough climate, and you have to work extremely hard at it. You have to reinvent all the time, coming up with ideas, trying to be everywhere and making sure that we're staying out there and trying to be talked about. It's constant, there’s no relaxation around it.

Pubs are multifaceted now. At The Orange, for example, we’ve got four bedrooms so you can stay, we've got a terrace, a private dining room, a first-floor restaurant as well as dining on the ground floor. Downstairs, we've got The Blood Orange Bar, which is its own separate entity. You can come here and have a snack or something a bit more formal, or you can have drinks. You can spend as little as you want within reason or as much as you want - they're democratic in that respect. They're quite nice areas that we're in, but we're still trying to keep that democracy, everybody's welcome. That's what I like about pubs.

The menus draw on my past career. At The Orange, it's Italian at the base with a few Mediterranean flavours. It's a similar vibe at The Princess Royal, although we don't have pizzas there. It's Notting Hill, it's naturally a bit more feminine. It's got a big terrace at the back and the nature of the place just suits a Mediterranean feel to the menu, so there’s things like chicken Milanese with datterini tomatoes, slow-cooked with thyme and garlic, and a rocket and oregano salsa verde. We have a raw bar there with crudo and oysters.

The Thomas Cubitt is a bit of a blend of British and Mediterranean. That's dictated to by the head chef who worked for Mark Hix and at Spring. There'll be a steak, pies and a scotch egg, but you'll also have some more Mediterranean-style plates, it kind of feels right for the place. The pubs in Mayfair and Marylebone definitely feel more masculine, more chop house in style; The Barley Mow has a carvery.

The head chefs have a lot of autonomy now, whereas when they first started, it was a bit more tight reigned. We’ve built a relationship, we've got head chefs now that have been with us pretty much for three years, and they know what they're doing. For me, it's just about a bit of guidance and direction, but it’s over to them, and ultimately, it’s better because they own it and have passion for it.

I still get behind the stove a little bit. We did an event at the Alfred Tenyson and I was involved there, getting in everybody's way, that's probably what I was doing. I can't run about like I used to. But there's always something going on; we do lots of chef collaborations, so when those things happen, I’m there. I get a bit more involved with the menus at The Orange and The Princess Royal, particularly with the styling, just because I suppose it ties in a bit more with me. The other ones, it's literally a tasting and then mentoring.

I still do my writing, so I'm still cooking quite a lot with that when I'm doing the recipe testing. I don't want to lose that because I find it enjoyable and quite therapeutic. If I'm doing dishes at home for books, there'll be some stuff that I'll pull out and say to the chefs, “Have a look at this, it might work”.

We are quite strict on our criteria when it comes to new sites. There's lots of pubs out there, but would we want them in those areas? There's not a huge amount of pubs coming up in Zone One. If we're looking at somewhere else, we want to have bedrooms because that's profit straight away. But we've got lots of plans. I want to be able to grow, I find that really interesting.’

cubitthouse.co.uk

Follow Ben Tish on Instagram: @ben.tish

Watch Ben’s monthly Dish with Tish recipe videos on Cubitt House’s Instagram: @cubitthouse

The Dishes

Crown of asparagus, The Ritz, London (early 90s)

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

The background

I’d worked for Jason Atherton for about a year in Skegness, which is where we’re both from. He'd already been in London and worked for Marco Pierre White, Nico Ladenis and Pierre Koffman. Then he'd moved back to Skegness at the age of 22, so still really young, and decided to take over the restaurant at this local hotel where my parents used to go drinking called The Links. It was a golf hotel, really naff. I was at a loose end, bumming about basically, and I ended up being his kitchen porter.

He was literally cooking straight out Marco's cookbook. He gave me the passion and I fell in love with it. We were just there all the time, but the maximum we would do was 10 covers, nobody was interested, so Jason offered to get me a job in London at The Ritz with David Nichols. It was a real culture shock. I kind of thought that, after working with Jason for a year, I knew a bit, but it was just a different thing. I was there for a year and a half on the larder section and hated every single day of it. There wasn’t a day that went by that I didn’t feel like I’d made a big mistake. I missed all my mates, it was really hard work, I was at the bottom of the ladder and I was really not qualified to be there.

The dish

Part of my role was looking after the Palm Court, which is the afternoon tea sandwiches and all of that, which was hellish. But my real nemesis was the crown of asparagus. Everything was built to order and I just remember shaking trying to put the dish together. You'd have to put a ring, which was a cut piece of pipe, on a plate, and then you'd have these halved asparagus spears that you used to have to build around the outside, then fill it with a lobster mousse. Then you had to carefully half-lift the pipe off and use blanched chives to tie the crown so it stayed together. I would just mess up all up and it would take so long to do. When one came on order, I was like, oh God. In the end, it became a little bit of a joke. I was a clumsy chef. It was a dish that I never got right. They were formative years, but I couldn't see myself going in that fine dining direction.

Tomato Risotto, Coast, London (1995)

The Background

The hotel in Skegness didn’t work out, so Jason moved back to London. Oliver Peyton had just opened Coast and Stephen Terry was the chef there. Jason went and joined him as senior sous chef. Jason called me up and said, ‘Do you want to come and work, it’s quite cool’. It was Oliver Peyton in his heyday, just after the Atlantic. It was designed by Marc Newson, it was groundbreaking. I didn't have any contact with him at that stage, but I am actually mates with Oliver now. He was a real visionary. Some of the things he did as an early entrepreneur were amazing; he was the first person to import Absolute vodka to the UK. He was a very stylish person, you’d see him walking around in these amazing Comme des Garçons suits.

When I joined Coast, I started to feel a bit more passionate. The Ritz was just a job, but at Coast it was such a small, tight team - good chefs and all very nice. I'm still in touch with everyone as friends. Steve was a great chef. Quite chilled out compared to a lot of chefs at that time, but there was really good team there, including Elliot Ketley (now at The Ship, Brancaster), Hywel Jones (now at Restaurant Hywel Jones, Lucknam Park), Maria Elia (now a consultant chef), Dan Lepard (now a cookbook author among many other things) and Mark Sargeant (most recently at Restaurant MS in Folkestone, now closed). When I started, I was commis on the sauce section and Mark was the chef de partie. Everybody used to party as well; it was that kind of era. It was just great.

The food I thought was really interesting, I guess you could say it was Pacific Rim cooking. Steve had worked in California and a bit in Australia, but he'd also worked for Marco and at Le Gavroche. The food was quite groundbreaking at the time. It took its inspiration from everywhere; there was Italian on there, but also a lot of Asian influences, it was just really exciting. I was there for two years, it was such an inspiring place. The only reason I left was that there was a changing of the guard, and Bruno Loubet took it over.

The Dish

The tomato risotto was on the menu consistently. It was a signature dish and I used to make it. It was when risotto cakes were very on-trend. The risotto was made with just onions, garlic, rice, tomato stock infused with basil, Parmesan and butter. It was set in a tray, and when it cooled down, you'd cut it out into a square.

To order, you would flour it and pan fry it in butter so you'd have a crispy risotto cake. Then you put it on the plate and put a square cutter over it, which would fit the risotto. Then you'd make to order a salad of goat’s cheese, avocado and tomato concasse. You would mix that with vinaigrette, put that in the square on top of the risotto so that it was flush and remove the cutter.

Then you'd put on a really tall rocket and Parmesan, balsamic and olive oil salad on top of that. Very nineties. We used to make hundreds and hundreds and hundreds. It was a really good dish. Tricky as well. Steve used to like it really tall, he loved stuff that was over the top. You’d get busy, and by the time he’d checked it, the salad would have fallen over, so you’d have to do it again.

Reginette all'uovo con piselli e pancetta, Al Duca, London (1999)

The Background

After I left Coast, I went to L’Oranger in St James Street with Marcus Wareing. I was there for about four months. I didn't enjoy it. Looking back on it, it was a mistake. I felt a bit of pressure, after having a chat to Steve and Jason and them saying the next thing you need to do is go into Michelin. Marcus was rocking and rolling in terms of everybody in the chef world saying it's the best place and he's the best cook. Through Steve, I was able to get a position there quite easily.

I stuck at it for as long as I could. It was out there, it was tough. It all stemmed from the top and the culture there. It was one-upmanship - I was treated terribly, and it wasn't just me. It taught me that I would never run a kitchen like that. I was afraid to go into work, and there was lots of jostling and all that kind of thing. I didn't respond to that. I get quite nervous, I've always been a bit like that, even when I was at The Ritz. It's not effective. It makes you nervous, it makes you on edge, and then ultimately you make more mistakes. It's just a vicious cycle.

When I was there, I was 22 and Marcus was 26 as a chef patron. He was put in that position, but he didn't know how to manage a team then. Who does at 26? It's really rare, especially when you've got to focus on making sure that every dish goes out the same. But things have changed; that was a different era. I'm really careful with promoting people. It's got to be considered because it can be dangerous.

I then went and worked at One Lawn Terrace in Blackheath with Jason. It was only open for a year. It was kind of like Coast, it was the same kind of food. Then Steve opened Frith Street in Soho with restaurateur Claudio Pulze. Jason went to be senior sous and that was again a really good period but very, very tough. Steve was running it like when he was working for Marco. It was a much smaller kitchen than Coast, and it was more fine dining. We used to make everything from scratch, including the bread. Everybody worked every day apart from Sunday; you were there from seven o'clock in the morning till 11 o'clock at night. I learned loads in that period. I worked on the sauce section with Jason. Everything had its own sauce; duck sauce was made with duck bones, pork bones for pork sauce and so on. It was a ridiculous workload for the covers - we do 20 to 30 at lunch and maybe 40 to 50 at dinner, perhaps maybe a bit more on the weekends.

I went to Al Ducca because Steve Terry was asked to move on from Frith Street because it wasn't making any money. Jason became head chef and simplified it massively with more crowd-pleasing stuff. Then Claudio said to Jason, ‘We're going to open a restaurant with you called Anise, but it's going to take a few months to open, so we're going to need to filter you and your team out into the group.’ So I ended up going over to Al Duca.

I suppose I was a bit sceptical about Italian food at that time. It wasn't really a thing back then. It was very simple food at Al Duca, two or three ingredients on the plate, but actually brilliant, it was really good. Michele Franzolin was the chef, and he'd worked for Giorgio Locatelli, so it was northern Italian. All the meat and fish was cooked on the charcoal grill, which was completely new to me; I’d never worked with one before. Now it's ten a penny, but at the time it was really unusual. It was an all-Italian team apart from me, and they were lovely.

They had a pasta room where they were turning out tagliatelli, spaghetti, and ravioli. I’d made ‘French’ fresh pasta with Steve, but this was in an Italian style, so much more rustic. Honestly, I found my calling there; it was so good. What was really interesting was how authentic and genuinely passionate they were about the food, the seasonality, and the ingredients. I’d not had that at any of the other restaurants, really. We never talked about seasonality or anything like that. At Al Duca, they'd get excited about a box of lemons coming in.

I just thrived there. I just fitted in. I had a bit to give because, whilst I didn't have much knowledge of Italian food, I had quite a structured background from working with Steve, so that helped shape the kitchen. I decided to stay and didn't go back to work for Jason at Ansie, which I think he was a bit cheesed off about. I ended up being the head chef.

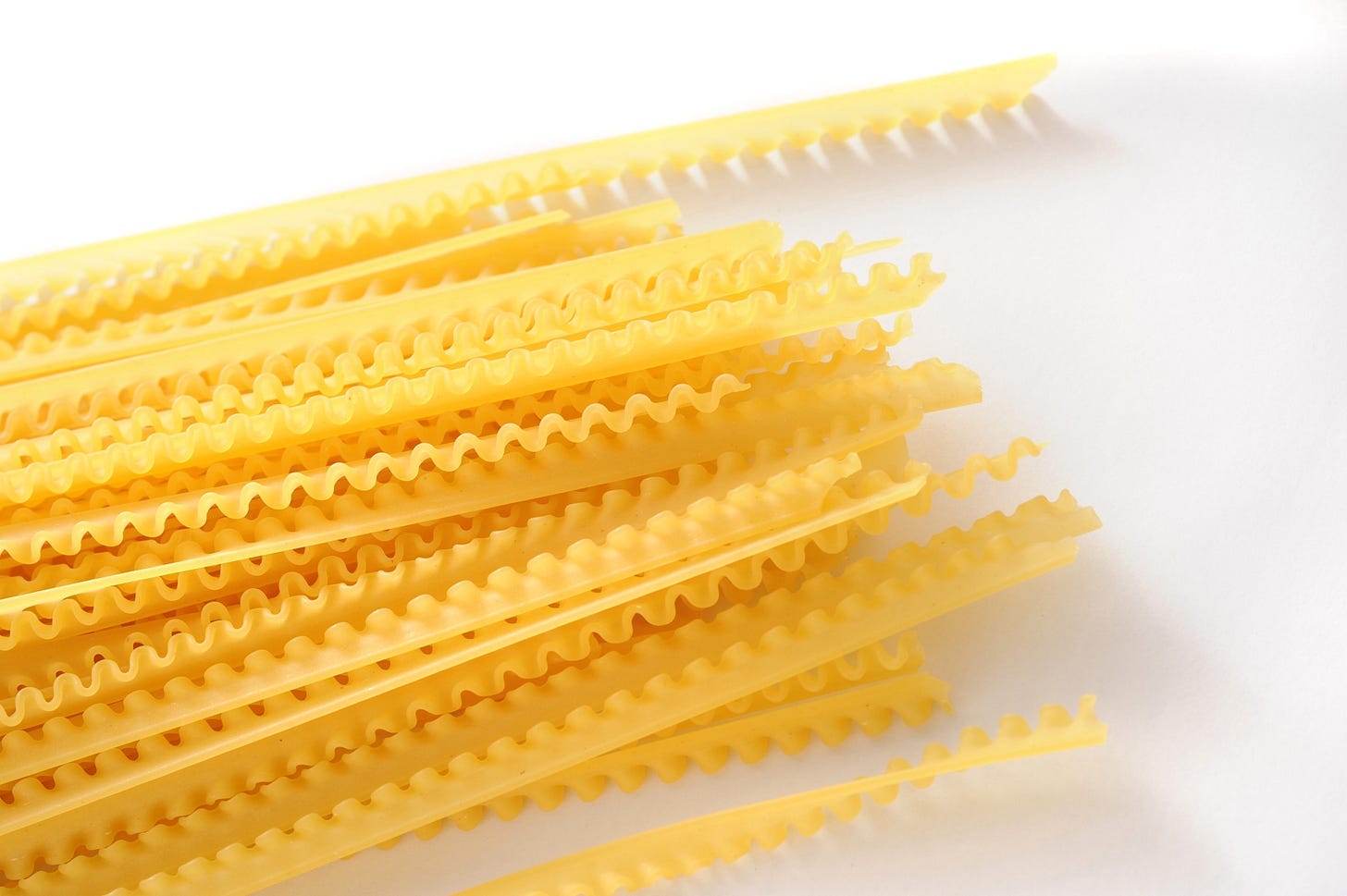

The Dish

The signature dish there was the Reginette. It's a long pappardelle-type of pasta, but with cuts in it. Reginette refers to regal like a crown. You cooked the pasta in a pan, then sweated cubes of pancetta down to release the fat. The pasta would then go into the pan with the pancetta with some pasta water, and a ladle of beurre blanc. You’d toss it through so it was all coated, then add fresh peas. To serve, we’d put pea puree on the bottom of a plate, then add the pasta and put rocket on top and that was it.

The beurre blanc was an eye-opener for me because it introduced a bit of classic French cooking. That must have come from Locatelli because he worked at the Savoy. That was the hit dish; we couldn't keep up with that. When we have a pasta dish on any of the Cubitt House sites, we’ll do a beurre blanc. What's good about it is that it’s a rich coating sauce, but you've got that acidity from the vinegar reduction that cuts through. It's a really good sauce for pasta.

Courgette flower tempura, goats cheese and honey, Salt Yard Group, London (2005)

The background

After Al Duca, I went to Scotland for three years as head chef of the Crinan Hotel on the west coast. It was an incredibly hard place to run. It was very seasonal. It was dead in the winter and then the summer was packed. There was a seafood restaurant on the top floor, an a la carte restaurant called The Western on the ground floor and a pub, The Panther Arms. It gave me a bit of a platform and got a bit of recognition like Best Newcomer in the Good Food Guide in Scotland, which was amazing. I was not expecting that at all. We got a couple of good reviews in The Scotsman and The Herald, but ultimately it was never going to be, I had to go back to London.

I had probably about six months off to go and check out what was going on. I'd been away for three years, so I was eating out and about. I was thinking about going to work for Jason, he’d just opened Maze time, and then Salt Yard came up. I got an introduction to Sanja Morrison and Simon Mullins, who we're opening it. At the time I'd been looking at places like Moro and I think Fino had just opened. The original concept was small plates with tapas, taking its inspiration from Spain and Italy, so I thought that was quite interesting. I went and cooked some dishes for them. They loved it. The two people who were in the running for the job were me and Nuno Mendes, but his stuff was a bit too wacky apparently. That was when he was doing syringes and all that kind of stuff.

I got on really well and ended up staying with Salt Yard group for 13 years. It was very much my project. It’s been the biggest thing in my career. I became a partner and I invested some money into it early on. We opened Dehesa in Soho after a couple of years, and then not long after that opened Opera Tavern in Covent Garden. That was quite unique. It was an old pub and we kept the bar. We used to have a beer pump, but it was a jamon leg cast in bronze. Then we opened Ember Yard in Berwick Street in Soho. That was based on trips that we'd had to San Sebastian. We got a grill made with the wheels that you would move up and down, and we were doing a lot of Iberico and also vegetables and fish. We were doing some smoking and all that kind of thing.

Then we opened Veneta in St James Market, which was a bit off piste for us. At that stage, Sanja had left the group. We took investment money and they were pushing us to do other stuff. We were focusing on kind of Venice and Northern Italy but it was a weird site and a weird location.

The Dish

Deep-fried courgette flowers was a dish we used to do across the group. They were stuffed with Monte Enebro, a Spanish goat’s cheese, which we found was perfect for it. We did a lot of research because some cheeses were too hard, some would just completely melt. All we did was cut the cheese, roll it into a ball, take the stamen out of the flower, pop in the cheese and twist the flower so it would stay shut. You'd have to make sure the flowers were left out for a couple of hours so that the petals would start to wilt. If they were too fresh, you’d snap them. We then slit the stem so that it would cook evenly and deep fried it. You’d have two of those deep-fried in a light tempura-style batter, drizzled with honey, that was it.

We sold hundreds of thousands. Even though courgette flowers are a summery thing, we’d have them on all year round. We just couldn't take them off. We probably sold more in the winter. We got them from Holland and Israel. A lot of my time was spent tracking down where to get courgette flowers. It was an ongoing thing and people couldn't believe how much we were using. They were on from the day we opened Salt Yard and we even had them on at Veneta. Salt Yard got sold to Urban Inns a few years ago. It's still going and they’ve still got the flowers on, which is fine, it’s a legacy. We have them on occasionally at the Cubitt House sites, but only in late spring, early summer.

Aubergine parmigiana, Norma, London (2019)

The background

It was tough opening Veneta. We spent a fortune on it. We were really under the cosh and we were then reporting into these venture capitalists. I remember one time I'd been at Veneta for two weeks solid and we had our monthly board meeting. They were giving us a hard time and I thought, I've just done two weeks, no break, opening a restaurant essentially for you and you've giving me this? The dynamics had changed from being a family business to that. Also, it was a long time to have been doing something and I felt that maybe we'd kind of reached the end of that period. My wife said, “You need to do something else”.

I had a year out looking at opportunities. I was close to doing completely my own thing. My wife was going to join me, but in the end it didn't work out. I got a backer and we were going to do a site in Soho, and that fell through. It was really disappointing, a real kick in the teeth. It's probably a good thing because looking back, I don’t think we could have worked together, my wife and I.

Then a friend of mine, Jo Barnes, who runs Sauce Communications, introduced me to Stuart Proctor, who was general manager at the Stafford Hotel. Jason Atherton was involved somewhere along the lines as well because they opened a restaurant called Game Bird at The Stafford and James Durrant, who was previously Jason’s head chef at Maze, was head chef there. So Jason was behind the scenes working with Stuart. James left Game Bird suddenly, and the deal was that if I came in as chef director and helped oversee the chef who replaced James, then we'd open a restaurant together.

My concept, which I'd got already, was Norma. I’d just released my cookbook Moorish, which was all about the Arabic influence on parts of the Mediterranean, including Sicily, and that was what took me in that direction. The original concept was going to be a Moorish restaurant, which would cover Sicily and parts of Andalucia too. I was thinking a bit like Salt Yard but with much more of that kind of spicing and the Moorish vibe. But I decided I would be more specific about the area because I felt that's what would work, so decided to just go focus on Sicily as there wasn't a Sicilian restaurant of note. Sicily is one of my favourite places, certainly.

That was my biggest passion project because I set it up from scratch, including the decor and everything. So they were true to their word, it was a joint venture. I was overseeing the Game Bird, which I wasn't that interested in; it was a quite formal hotel dining room basically. They did all right with it, and when it first opened it was good food. Jozef Rogulski was the chef there who was very strong, very classic. They had things like chicken Kiev, but done in a really fine way, and they had a smoked fish trolley. It was good.

Norma was my project. We did really well, we were really well received and then got hit by COVID. We got through that, and we did all the boxes that everybody was doing and we work quite a lot through COVID on keeping the Norma name alive. I loved Norma, so I was spending a lot of my time there, growing and promoting it. The owners of the Stafford wanted me to do other things. They opened this project called Gallio, which is a pizza place, and they wanted me to get behind it. They had somebody running it but I just couldn't buy into the concept. That was the beginning of the end for it really.

The Dish

Aubergine parmigiana was our standout dish at Norma. It’s quite classic in that we'd deep fry the aubergine, so it's quite a naughty version, then dredge them in fried breadcrumbs. We made it with burrata, tomato sauce, fresh basil leaves, seasoning and olive oil and layered it all up with the aubergines. We'd set it in a tray and press it. We'd take it out, cut it into thick rectangles and it would get flashed back through the oven with grated Parmesan on top. That would get set on the plate - it would be quite high with a real crust on top. Then we made a Parmesan sauce - basically reduced cream with loads of Parmesan in it so it was quite thick. That would go on the plate, and then more grated Parmesan and some basil on top. It was quite simple, but it was very rich and indulgent. It was delicious, most of the time, depending who made it, but it typified Norma and everybody who came had it and they loved it.

Three recipes from Mediterra

Kerkennah-style grilled prawns

Southern Shores – Tunisia

On the Kerkennah islands just off the coast of Tunisia, seafood is often paired with kerkennaise, a spiced tomato sauce with subtle chilli heat, pungent spicing and lots of spring onions, olives and capers. It is a sublime mix of Moorish and Mediterranean flavours. Use this sauce for any grilled fish, squid or octopus.

Serves 4; the sauce makes about 200ml

16 large Atlantic prawns, heads removed and the tail shells peeled off

olive oil

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

For the sauce

10 spring onions, white parts chopped and green ends thinly sliced

2 plum vine tomatoes, cut into large chunks

1 large green chilli, trimmed, quartered lengthways and deseeded

1 garlic clove, crushed

½ teaspoon ground coriander

½ teaspoon caraway seeds, lightly ground

½ teaspoon cumin seeds, lightly ground

2 tablespoons red wine vinegar, such as cabernet sauvignon

a handful of pitted green olives, chopped

a handful of flat-leaf parsley leaves, roughly chopped

1 tablespoon tomato purée

extra virgin olive oil

First make the sauce. Blitz the spring onion whites, tomatoes, green chilli, garlic, ground coriander, caraway and cumin seeds and vinegar together in a blender. Transfer this mixture to a bowl, stir in the spring onion greens, olives, parsley, tomato purée and a good splash of extra virgin olive oil. Cover the bowl with cling film and let it rest while you heat the barbecue.

Light the barbecue about 30 minutes before you want to cook so the coals turn ashen grey and are at the optimum grilling temperature. Position the grill above the coals so it gets very hot. Alternatively, heat a large ridged, cast-iron griddle pan to maximum.

When you’re ready to grill, pat the prawns dry, then rub them with a little olive oil and season with salt and pepper. Place on the grill and grill for 3 minutes on each side until the prawns change colour and are cooked through – a little charring adds a smoky flavour.

Transfer the prawns to a serving platter or individual plates and spoon over some of the sauce. Serve the remaining sauce on the side for everyone to help themselves.

Spinach, fennel and herb pie

Islands – Crete

I love this Cretan-style pie with its rich and crumbly olive oil-based crust. I’ve eaten many versions on my travels and the options for predominantly vegetable-based fillings are plentiful – courgettes, kale, green cabbage and even diced squash or pumpkin. Aleppo-style pepper and cumin are also often used in the spicing.

Sesame seeds are regularly used in Cretan cuisine, a legacy of its Moorish occupation, adding a sweet, caramelly nuttiness to the pie crust when baked, which I very much like.

Serves 8

100ml olive oil

2 fennel heads, finely chopped

2 red onions, finely chopped

1 leek, washed and finely chopped

a bunch of spring onions, finely chopped

1 teaspoon fennel seeds

500g spinach, washed and finely chopped

fronds from a bunch of dill, roughly chopped

leaves from a bunch of mint, roughly chopped

100g feta, drained and crumbled

2 large free-range eggs, beaten

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

For the pastry

500g plain white flour, sifted, plus extra for rolling out

1 teaspoon table salt

200ml olive oil, plus extra for greasing the pie dish

200ml lukewarm water

1 large free-range egg, beaten, to glaze

2 tablespoons sesame seeds

Heat the olive oil in a large saucepan over a medium heat. When it is hot, add the fennel, red onions, leek, spring onions and fennel seeds, and season. Turn the heat down to medium-low and leave to sweat for 30–35 minutes until softened but without colour. Stir often as you go to avoid anything sticking. When everything is softened, turn off the heat and stir in the spinach, dill and mint. Season again.

Let the vegetables cool completely before stirring in the crumbled feta and eggs. Set aside at room temperature.

Meanwhile, make the pastry. Place the flour and salt in a bowl. Make a well in the centre, add the olive oil and water and gradually work this into the flour to form a soft dough. Don’t overwork the dough as it can become heavy. Cover and chill for 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 200°C/Fan 180°C/Gas Mark 6. Grease a round 25–30cm pie dish.

Lightly dust a work surface with flour and then cut the dough into 2 pieces – you want one piece slightly larger for the pie base. Roll out the larger piece in a circular motion until it is about 0.5cm thick, dusting with more flour as you go. Fold it over the rolling pin and then roll into the pie dish. Press the pastry into the side well, leaving an overhang. Spoon in the vegetable and feta filling and spread it out evenly.

Roll out the remaining pastry until 0.5cm thick and lay over the top of the filling. Pinch the pastry edges together to seal the pie, then trim off the excess pastry. Brush the top with beaten egg, sprinkle over the sesame seeds and poke a couple of holes in the top to let out excess steam.

Place the pie dish on a baking sheet and transfer it to the oven. Bake for 1 hour, or until the pastry is golden brown and crisp. Leave to stand for at least 5 minutes before serving. It’s equally good served hot or at room temperature.

Roasted tuna with baked tomatoes and basil

Islands – Sardinia

Tuna fishing is taken very seriously in Sardinia. The annual Carloforte tuna catch is renowned worldwide and takes place from late April through to early June. The fishermen use the only ‘tuna trap’ method of fishing still in practice – a method invented by the Arabs in the Middle Ages that uses a series of net trap chambers to catch and haul the fish to the banks of the port. People come from far and wide to see this macabre spectacle and it is considered cruel by some. This technique, however, is more humane than many other modern methods and the catch levels are monitored to ensure there is no overfishing.

This recipe is similar to one that I first tasted in Sardinia – very simple, using the best-quality fish and ripe tomatoes in season. Try to get thick tuna steaks as they will be easier to cook and allow you to achieve a nice crust on the outside and retain a lovely pink colour on the inside.

Serves 4

500g vine tomatoes, cored and cut in half widthways

2 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

1 teaspoon coriander seeds, lightly crushed

2 tablespoons red wine vinegar, such as cabernet sauvignon

olive oil

4 x 200g tuna steaks, each about 2.5cm thick

leaves from a small bunch of basil

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 190°C/Fan 170°C/Gas Mark 5.

Place the tomatoes in a roasting tray, sprinkle over the garlic, coriander seeds and red wine vinegar, add a good drizzle of olive oil and season well. Transfer to the oven and roast for 25 minutes, or until the tomatoes have started to caramelise and release their natural juices. You’ll have a lovely self-made dressing in the pan from the mix of the oil, juices and vinegar. Leave in a warm spot.

Pat the tuna dry, then season each steak with salt and pepper. Heat a good splash of olive oil in large sauté pan over a high heat. When it is hot, add the tuna and fry for 2–3 minutes on each side to achieve a nicely caramelised crust. Remove from the pan if you like your tuna pink inside, but if you want it cooked more, cook it for a further 2–3 minutes, turning it as you go.

Rest the tuna for a few minutes before serving.

Meanwhile, gently stir the basil leaves through the roasted tomatoes. Divide among individual plates, then top each portion with a piece of tuna and spoon over the tomato-vinegar juices. Serve.

Recipes extracted from Mediterra by Ben Tish, published by Bloomsbury Absolute, £26. Photography © Kris Kirkham. Buy the book using the following affiliate link to help support Smashed (and make Ben’s day, probably): click here to buy now.

My lunch with Ben

An information-dense write up Andy—well done!

Romano Peppers according to the menu, but they do look great.